Tencent, China, and The Circle of Competence

I have been researching and studying Tencent over the past 1 - 1 ½ months – hence the lack of write-ups. It is clearly a huge, remarkable organization, and I have no doubt in the quality of the business or the capital allocation skills of Pony Ma and his team; however, the fact that I know that it is a good business at a decent price does not allow me to comfortably invest in Tencent.

This inability to “pull the trigger” primarily stems from the overall complexity of the company. Investing in Tencent inherently means placing bets on things that I have no right betting on. Regulation, competition, threat of innovation, and geopolitics all play a role in both the thesis and the valuation – no matter how much I don’t want them to.

As investors, we generally want growing and highly-predictable streams of free cash flow. So, having something like regulation threaten the competitive advantage of the business also impedes our ability to predict future earnings/ FCF to a relatively high degree of certainty. I ignored this issue when I invested in Alibaba, but have come to understand that regulation can (and does) affect the intrinsic value of the company.

If the government passes a law that 1) narrows the moat of the business (defensibility and predictability) and 2) influences the earning power of a firm in an unpredictable way (growth and stability) then we end up with a valuation that is rendered useless. Regulation isn’t something that we can easily model or “price in” – perhaps only through demanding an above-average margin of safety – and yet it can easily affect intrinsic value over the long-term. Given that Tencent is so closely tied to everyday life, even the regulation of industries like education and health care (where Tencent doesn’t really have a presence) affect the company through a decline in advertising revenue. Simply put: there’s no easy way of going around solving this issue of uncertainty.

As I was reading up on Tencent, I constantly made notes on things to research further. By the 3rd week of research, however, I have found that the list of things to do and learn only increased exponentially. It was sort of like Po in Kung Fu Panda where he’s struggling to make his way up the stairs, only to find as he looks down that he’s made just the first few steps.

What’s more, not only do I have to analyze the quality of each of Tencent’s main businesses (most of which are of very high quality) but I also have to look at the regulation and competition surrounding all these products and services. Competition in China is – in my opinion – much tougher for internet companies compared to that in the US. The market is crowded with cheap copycats and emerging players in industries that (for the most part) are still in a relatively early period of growth and development. Tencent itself could be deemed the “ultimate copycat” given its history of replicating products and developing them in a superior way to surpass competition. Trying to understand the dynamics and underlying trends of the market and the competitors is something too far outside of my circle of competence.

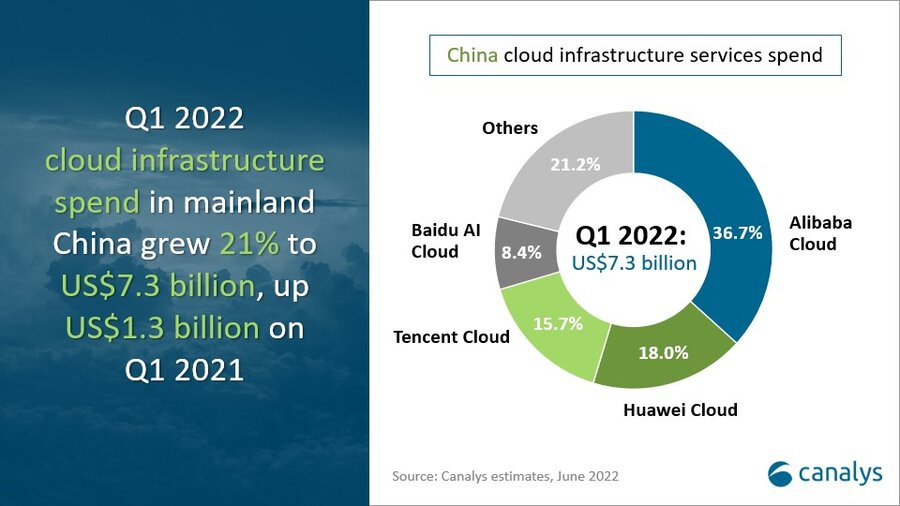

Each product would require careful analysis of regulation, competition, and trends. Sure, I can try and do that for WeChat, but analysis for segments like “Business Services” or even “Cloud” (these are reported together but could be analyzed separately) is significantly harder. It might sound ridiculous to call these segments “nascent,” and yet that is – to an extent – what they are. Such segments are in a stage of rapid growth and yet most lack a strong incumbent in an industry that is defined by economies of scale and network effects. Baidu or Huawei could theoretically end up as winners, or Alibaba can end up growing its already dominant market share and gradually push others out. I – again – lack the ability and the foresight to be able to determine which player will emerge as the winner (as one undoubtedly eventually will).

Even after reading several books on Tencent and the history of China’s internet industry, flipping through annual reports, reading earnings call transcripts, looking at numerous fantastic write-ups, and talking to some people, I still feel like I simply don’t have enough information. To comfortably invest, I would have to have an above-average understanding of CCP’s regulation, the competitive landscape, the underlying economic and demographic trends, and the possible threat of innovation that Tencent is subject to. In essence, I have no “edge” when it comes to understanding Tencent (or China in general), only a contrarian approach which I believe is unwarranted in this case.

There are so many wonderful things about this company. On the business side we obviously have the network effects, economies of scale, switching costs, and barriers to entry (infrastructure investments, license applications, etc.) Another source of competitive advantage stems from Tencent’s human capital. From Allen Zhang to Pony Ma to the numerous video game studios, Tencent has some of the best and brightest in a business where workforce quality, creativity, and flexibility greatly matter. What makes a video game studio successful if not superior programming, design, and development – all of which stems from the people behind the studio? We also get (almost as a side-bonus) one of the world’s best investment vehicles. In fact, it is a vehicle that has the unique ability to substantially grow initial investments on its own. From its WeChat platform which essentially controls user traffic in China (+ Mini Programs) to its experience and expertise, Tencent has a history of going out and turning start-ups into corporate behemoths.

On top of all of this, we have numerous products and services that are under-monetized – a result of management’s focus on user experience and long-term competitiveness. From video games to ads, Tencent can theoretically turn on the switch like Meta or Electronic Arts/ Activision and go heavy on monetization, resulting in greater profits now but poorer CX over the long-term. Pony Ma prefers to buy and leave – sort of similar to the approach Buffett takes. When acquiring a video game studio, for example, it is said that developers tend to retain a high-degree of autonomy and pursue projects that they themselves find worthwhile. Now, however, they also have the resources and financial backing of the largest developer in the world.

It’s not necessarily all of the above issues that don’t allow me to invest in Tencent. For example, although I don’t know who will end up as the winner of cloud, I know that Tencent will most likely benefit from the growth of the market in the long-term. Even though I can’t fully understand the market dynamics of each segment, I know I have a good enough idea of just how good some of the businesses are (primarily WeChat and Gaming). VAS has seen tremendous growth in subscriptions thanks to Tencent Music and Video, and this should likely continue well into the future. Instead, it is simply the fact that I likely won’t know “enough” to be very comfortable investing. I’ll probably never have an edge, and I think there are opportunities out there that I understand much better that still offer a similar risk-reward proposition.

Complexity is often a good thing, as it gives us a chance to dive deep and uncover a thesis that others have simply neglected. It should, however, be a complexity that we can “understand” (and I mean REALLY understand), or we will inevitably get burned. Although I’m sure there lies a thesis somewhere out there for Tencent – and I’m sure many have already found it – I simply lack the needed tools and knowledge to be able to get to that thesis, no matter how hard I try to force my way through the plethora of information.