Humansoft Holding Company (HUMANSOFT.KW)

Worth taking a look, but this one's not for everyone

Overview

Humansoft owns Kuwait’s #1 QS-ranked university, AUM (and ACM), with ~13,750 enrolled students, 12,000+ alumni, and 1000+ faculty and staff from over 70 countries. American University of the Middle East (AUM) is ranked 24th among Arab states and is one of a few Kuwaiti universities with a 5 stars from QS. Revenue has grown 23% CAGR since 2013.

Kuwait, as we will discuss later, has a large and increasingly challenging problem within its education system. This issue, in turn, has formed a large institutional tailwind for Humansoft.

The education industry has seen some negative investor sentiment over these past couple of years. From China’s regulation which sent shares of companies like TAL Education crashing to the scandals and controversy surrounding US-based for-profit institutions, many are of the opinion that it is better to stay away from education-related companies. I disagree.

Some, like Humansoft, are actually solving large and complex issues – issues even the government can’t fix. Since the beginning of the 2000s, private universities have started popping up across Kuwait, and many have benefited historically from problems surrounding Kuwait’s public universities.

Founded in 1994 as “New Horizons,” the company was initially a modest computer training center. This business still exists to a certain degree, but it is essentially negligible in relation to the size and profitability of its university business. In 2003, the company invested in Net G – an e-learning company. This investment would complement the existing line of business, and would push management in the direction of building an actual institution to make use of all the technology and experience the company gained over the years. AUM was launched in 2006, and ACM followed in 2008 after partnering with Purdue University. We will get to the two shortly.

Kuwait and Its Economy

Kuwait, as most already know, is a small country located in the Arab Gulf region. Despite a population of just ~ 4.3mm, the country’s GDP exceeded $140b in 2021. For reference, Kazakhstan, with a population of ~ 19mm (or over 4x that of Kuwait), has a GDP of $170b. The country, like most other Arab states, has benefited significantly from large oil reserves (Kuwait, according to some estimates, possesses around 6% of the world’s proven reserves).

The country is an “Emirate,” or a monarchy, with the House of Sabah serving as the ruling family. It is also one of the only countries (along with Bahrain) that have a legislative branch. This, however, serves as a double-edged sword as we will come to see later on.

After the Iraq-Iran war of the late 80s and early 90s, Kuwait has seen a period of war and border-disputes. Iraq – partially due to disputes over the $65b debt Iraq owed to Kuwait – invaded its neighbor in August 1990 and annexed it within just 2 days. Half of the Kuwait’s population, along with members of the ruling family, fled to safety. The UN would go on to sanction Iraq and UK and US troops would deploy forces in Saudi Arabia and take back the territory. Border disputes would prevail post-war, partially triggered by the UN’s shifting of the border to grant Kuwait several more oil wells that were previously on Iraq’s territory.

The country has largely recovered, and has seen a period of relatively strong growth. Women gained the right to vote in 2005, and the government would go on to build out infrastructure and reinvest its oil profits into the economy (at various degrees of success). The country has also amassed one of the world’s largest sovereign funds in the process.

Despite all of its investments, Kuwait still remains severely underdeveloped in many respects relative to its Arab neighbors. Infrastructure is lagging behind, human capital is a large issue, and education is one of the worst despite the government spending more (% wise) compared to the GCC average. The country spent 6.6% of GDP on education vs. 4.8% among GCC states.

Demographics are very favorable. Roughly 25% of Kuwait’s population is under the age of 15, 15% between the age of 15 and 24, 52% between the age of 25 and 54, and the rest are aged 55 and above. Despite enjoying a very young population, Kuwait is seeing issues in developing a private sector. In fact, 81% of Kuwaitis are employed by the public sector, where people generally earn higher salaries, get better benefits, and experience greater job stability. This has resulted in a whopping 55%+ of government expenditures used towards paying salaries.

This dependence on the public sector also has some long-term implications regarding education. The population is generally comfortable knowing that there is a well-paying job out there (provided by the government) waiting for them. So, most go to college just for the sake of earning a degree – not obtaining knowledge.

COVID-19 has also taken a fairly large hit on the country’s economy. Not only did oil revenues decline, but the government was forced to spend more to alleviate the impact of the virus on the population and the economy. The country faced a budget deficit of $46b in 2020, and has resulted in the government’s tapping into the General Reserve Fund. Although current deficits aren’t anything alarming (and there are plenty of countries with deficits exponentially higher), this again shows the need to diversify away from oil and, in turn, means that the government should be diligently working on building up a strong and self-sustainable private sector. The sector today plays a minuscule role in the economy and, even then, is heavily dependent on government spending.

Management

It’s fairly hard to find any meaningful information on management, and there aren’t any transcripts I can read to get a feeling for their philosophy/ strategy.

Having built one of the best and largest universities in the country from scratch definitely indicates a certain level of experience and competence. We have to keep in mind, however, that a large part of this growth is thanks to issues with public education, and the government's decision to start giving our scholarships to attend private colleges. Mayank Baxi was the CEO until 2021, when Dr. Yahchouchi took over. Yahchouchi has previously been the CEO of AUM and has a Phd in business from Montesquieu Bordeaux University (2004), “Learning and Teaching in Higher Education” degree from University of Chester (2013), and “Professional Education Certificate in Institute of Educational Management” from Harvard Graduate School of Education (2019). Clearly, he is someone who has a lot of experience in the industry (unlike some of the policymakers in the Ministry of Education) and knows how to run a business given the growth and success of AUM under his leadership. The current Vice Chairman – who was the Chairman for a fairly long period of time – Fahad Al-Othman also seems like someone very competent and capable. He is on the Board of Trustees at AUM and likely helps Dalal Hasan Al Sabti (current Chairman) with her decisions. Here’s an interesting video I found:

I think it makes more sense to evaluate management from its actions (as there really isn’t much to go off of other than that). Since established AUM and ACM in the mid-2000s, management has successfully grown the two institutions (which are theoretically just one) from essentially nothing to a 13,750+ institution that is ranked higher than even Kuwait University, the country’s largest and oldest institution.

If we look at the rankings, we could also get a fairly good idea of how management has performed. In 2021, AUM was ranked #801-1000 in QS. In 2022, it was ranked #751-800. This year, it’s rank once again increased to #701-751. Clearly management is doing something right to warrant this change. AUM is the #1 university in Kuwait for 2 years in a row now, and is #1 in “Engineering and Technology,” as well as “Social Sciences and Management.”

They are doing a good job. Some reviews on Glassdoor cite micromanagement and high turnover within the university, but I don’t see that as a necessarily large issue.

Capital allocation seems decent. It obviously wouldn’t make sense to open a new college in the country as that would essentially be cannibalization + it makes more sense cost-wise to just introduce new majors/ schools within the existing infrastructure, which is exactly what management has been doing. Humansoft has already, according to some filing and presentations, gained a license from the government to open a School of Health Sciences and a School of Nursing, both of which should enjoy fairly strong demand and boost the existing student base.

Based on the letter from both the CEO and Chairman in the most recent annual report, however, I find that management is unsure of what to do next other than expanding on programs offered by the school. Its ventures into e-learning have been mediocre at best (other than the fact that it does in a way boost the education quality of the existing university). It does have the only license to distribute courses by Skill Share in the country (and among the GCC states), but that again is mostly just additions to the university, and not a separate line of business that can generate any meaningful cash flows.

In a way, I don’t really blame management. They have built something that actually enjoys a fairly strong moat (both from the business and government regulation side). If it just continues distributing cash to shareholders and improves on the university, it should do just fine.

I do see a lot of potential in entering the K-12 market as the situation is fairly similar there, and I think returns on that project would be strong, but that is again up to management and largely depends on how it goes about building that. Building a school (or perhaps even a network of schools across the country) would also mean that they would have a strong pipeline of students for the university to accept. Enrollment rates are are substantially higher than those in higher education.

Like most other schools, AUM likely faces a shortage of quality human capital (hence, perhaps, the micromanagement within the university). Kuwait, on a country-wide basis, has a severe shortage of qualified teachers, and even larger shortage of local ones. This serves both as a good and bad thing. Obviously, education quality would improve with better teachers, but at the same time the university likely has better access to the higher quality teachers (as opposed to some smaller, less financially sound universities). This is in a way similar to what Kaspi enjoys where it gets the first pick on the best developers and programmers in Kazakhstan.

AUM

Now, let’s dive a bit deeper into the university itself. AUM and ACM have both been established through Al Arabia Ent. (subsidiary).

Established in 2005-2006, AUM is the largest private university in Kuwait, with excellent facilities (compared to the average university in Kuwait) including a library, sports center with a certified soccer field, and a cultural center with a theater scattered across a 261,000 m^2 plot of land leased from the government (the government owns 90% of the land in the country). The only two programs currently offered are “Engineering and Technology” and “Business Administration,” but AUM is considered among the best in both of these fields.

The business school is accredited by AACSB and the engineering school is accredited by ABET, both globally recognized accreditations. The university has also developed a strong liberal arts department that offers courses in social sciences, humanities, ethics, English and literature, economics, music, and so on.

Students have access to a soft-skills e-course (Humansoft’s initial line of business) with 7,000+ video courses. The university has partnered with numerous other colleges to expand its offerings without actually having to make the investments. For example, it has recently partnered with Babson to allow its students to enroll in the university’s masters program. Other partners include Purdue, UC Berkeley, HEC Montreal, CMS-CERN, and PRME.

ACM

ACM is, essentially, part of AUM (just like Harvard College is part of Harvard University).

In 2011, the Kuwaiti government issued a law that requires private universities to partner with one of the top 200 universities in the world. Established in 2008, ACM has partnered with Purdue, and its competitor, American University of Kuwait (AUK) has even managed to partner with Dartmouth. This again serves as yet another barrier to entry when it comes to entering the market.

The college essentially tailors to the preference of students to go for degrees based on careers (most students go to college to later earn a higher salary in the public sector). It offers a 2-year degree based on career-based programs which generally intersect with what AUM offers as a whole (Business, Engineering, Liberal Arts). It has developed an internal career-center to help students with finding jobs.

ACM has seen a decline in enrolled students since 2017 (from 2,286 down to 1,892). I’m unsure if this is because the students choose to pursue the full AUM program, or because of some other factor.

I think looking at AUM and ACM as a whole makes more sense, and the overall student enrollment, as we’ve seen, has been steadily growing over the years.

Competition

Since the first private university, The Gulf University of Science and Technology, was established in 2002, numerous other private institutions have sprung up across the country over the decades. Most prefer to offer several niche programs to avoid clashing with the larger universities like AUM. Kuwait isn’t like the US, and the pool of students is significantly smaller. There are only so many colleges that can just offer the most popular degrees and do fine over the long-term.

American University in Kuwait

AUK is perhaps the most direct competitor to AUM. It focuses more on liberal arts, but the program, philosophy, and offerings are very similar. The university has ~2,100 students and several hundred faculty members, so it is significantly smaller than AUM.

As previously mentioned, it did partner with Dartmouth which likely serves as a huge advantage when it comes to attracting students. AUK, unlike AUM, doesn’t offer any post-graduate programs.

AUM also offers more depth in the engineering and business programs, whereas AUK does better when it comes to liberal arts. Although it definitely puts some tough competition, the variation in program focus and size does differentiate the two a bit.

Kuwait University

Kuwait University (KU) is the largest university in the country with ~39,000 undergraduate and ~2,000 postgraduate students. Founded in 1966, the university has a total of 17 colleges.

KU was considered the “beacon of higher education, attracting college-level students from across the region well into the 1980s,” but slowly lost ground to other Arab state universities over time (as did Kuwait as a whole). Despite the rapid growth in size and infrastructure, numerous sources state that the quality of academic output has not kept pace.

KU is a public university, so the education philosophy and programs differ to an extent. There is a general perception that private schools are of “higher quality.”

Australian College of Kuwait

ACK is one of those colleges that offers niche programs. On top of the usual engineering and business majors, it also offers programs in Aviation and Maritime studies. Like the other universities, ACK did well in partnering with high-ranking institutions to bolster its reputation. In fact, it even works with Lufthansa Technical Training for its Aviation program. Partners include Central Queensland University and Aalborg University.

As we can see, there are several private school universities in the region, but only a few truly large players. Competition is also primarily local, and is largely based on quality of infrastructure and teachers, as well as the partners of the university.

Some may argue that other Arab state universities should also be considered as competition, but Kuwaiti students are going to face significantly larger costs (travel + living) as well as fewer scholarships when it comes to that region. Behemoths like King Abdulaziz University and Cairo University would be very tough competitors, but as we can see based on AUM’s growth + students’ preference to work locally (where salaries are better and job stability is greater) it makes sense for most to study within the country. Competition is primarily local.

Kuwait’s Education

Here, really, is what makes all of this click. Kuwait was one of the first countries in the Gulf region to shift from informal to formal education with the establishment of the Al Mubarakiya School in 1911 by local merchants. In the 1930s, the government took over education and made it free for all, introducing the Compulsory Education Act in 1964. With a more developed local school infrastructure, Kuwait would even help and advise other states in how to set up their own education systems. In the 1940s, the government decided to replicate Egypt’s education system, but policymakers didn’t account for differences in culture, demographics, and infrastructure. Thousands of Egyptian teachers taught in Kuwait, and many still do.

The goal of the government, at the time, was to simply boost enrollment and increase literacy rates. So, they would drastically increase the number of students in schools, but neglected the “quality” aspect of education. Education became mandatory from the age of 6 to 14, and a large number of teachers were recruited from abroad.

With an exploding economy thanks to its oil revenue, Kuwait would go on to develop a significant public sector. As we’ve already mentioned, over 80% of the population works for the government today. This, in turn, meant that most were not incentivized to study. An eminent Kuwaiti author and associate professor of English and comparative literature at Kuwait University commented that “many of the students I teach at the undergraduate level cannot read, write, or think critically. Most register in the Department of English Language and Literature because the public-sector job market offers competitive salaries for English-language speakers. There is a discernible apathy, a lack of engagement with ideas, and a desire to be rewarded good grades without effort.”

In fact, many professors today are pressured or bribed into improving their student’s grades. The lack of incentives could also be seen in AUM, where the female student body accounts for 60% of enrolled students, even though Kuwait is around ~ 60% male.

This unwillingness of students to study, matched with a poor education system that didn’t fit the needs of the country and its goal of building human capital and developing the private sector, resulted in a drastic deterioration of education quality in relation to other Arab states. Kuwait University doesn’t even make the top 30 of the universities in the region, despite being recognized as a leader decades ago.

Issues like these could be fairly easily amended with the right policies in place. The Ministry of Education (MoE), however, is unable to successfully implement the needed reforms. Political leaders in Kuwait tend to be selected based on loyalty and relationship to the royal family, wealth, or political connections, — not merit. Policy-makers at the top, according to numerous reports, might have no experience in education at all. Like with many other areas in Kuwait’s economy and political system, the MoE lacks quality human resources to be able to properly address the issues at hand.

The decision-making process is highly centralized at the top with a top-down approach. Mid-level leaders, such as district leaders and principals of schools and institutions usually don’t get a say in the process. The government also fails to properly analyze and evaluate the progress/ failures of its reforms, and hence is incapable of reflecting and responding to the problems.

As previously mentioned, Kuwait spends around 6.6% of its GDP on education vs. an average of 4.8% amongst the GCC states. MoE has sought advice from various international consulting firms and organizations over the years (UNESCO, World Bank, British Council, Center for British Teachers, McKinsey, Tony Blair, and so on), but even when a plan is made, implementation often fails. One study wrote that “the education system in Kuwait is similar to a “Snake and Ladder Game,” where the MOE takes a few steps forward and is then swallowed by the snake, which requires them to start from the beginning. If we evaluate each component in-depth, the main problem goes back to the MOE not being the party that was supposed to lead the reformation process in the first place.”

The most recent attempt has been the Integrated Education Reform Program (IERP). The plan was split into two stages, one from 2009-2014 and another from 2015-2019. The first stage focused on enhancing the school curriculum, developing school leadership, establishing educational standards, and strengthening the NCED (National Center for Education Development). The second stage focused on improving the quality of core education and achieving better results in international standardized testing.

In the end, almost every aspect of the program failed. From bureaucracy to poor execution, the government and the institutions involved were incapable of implementing the plan. What’s more, several aspects of the plan fell into the jurisdiction of a separate government body/ institution, making it impossible to go through. The IERP was suspended in 2019. The NCED, which the plan was supposed to strengthen, largely doesn’t even function anymore.

Kuwait consistently ranks one of the lowest in terms of education outcomes among the Arab states. Despite the fact that the government has kept claiming that improving education is one of its top priorities, it seems like that is not the case in practice.

Government Paralysis

As previously mentioned, Kuwait is one of the only countries in the GCC with a legislative branch. Kuwait doesn’t allow for formation of new political parties. The National Assembly (Majlis Al-’Umma) has the power to vote the prime minister and the cabinet out of office (both appointed by the emir). In November of 2019, for example, the prime minister and the cabinet resigned after mounting pressure from the assembly. Here’s what happened:

“The political crisis erupted when lawmakers started to question the interior minister, Sheikh Khaled al-Jarrah al-Sabah, over alleged mismanagement and misuse of public funds. When the parliament called for a no-confidence vote, the entire cabinet resigned. Soon afterwards, Sheikh Nasser Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah, who was also the emir’s son and had temporarily filled Sheikh Khaled’s vacant position, reiterated the claims of corruption against Sheikh Khaled. He claimed that he discovered embezzlements of KWD 240 million from the Kuwaiti Army Fund when Sheikh Khaled was defense minister (2013 – 2017).”

The majority of the power, however, still resides in the hands of the ruling family, with the emir capable of appointing the PM, cabinet, vetoing bills passed by the assembly, and dissolving the assembly (which has happened numerous times through the decade). The National Assembly does dilute power partially, but not to an extent that completely shifts the scale.

The main issue, however, is constant tensions between the legislative and executive branches. Constant arguing and tensions often paralyze effective policy-making and execution. This has, partially, played a role in preventing proper education reform.

In addition to this, we also have the MoE which tends to be inadequately prepared in solving existing issues regarding the education system. A study explained that Kuwait really has two options in effectively addressing the education problem: either restructure the MoE and rebuild human capacity or delegate reforms to another government body or outside organization. Neither, as you’d probably agree, are likely to happen.

After the death of the late Sheikh Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah on September 23, 2020, Sheikh Nawaf came into power. Before his passing, Sheikh Al-Ahmad implemented the “Vision 2035” plan, consisting of 7 pillars:

Global Position (trade, culture, diplomacy, etc.)

Human Capital (Plan on opening 13+ new colleges w/ 40,000 student capacity)

Healthcare

Living Environment

Infrastructure

Economy

Public Administration

The plan aims to transform Kuwait into an international trade hub and diversify away from oil revenue with the help of the private sector. With deficits remaining relatively large and fiscal buffers like the General Reserve Fund gradually getting chipped away, there is no time like now to start moving.

Business and Moat

Universities aren’t a fast changing industry. Threat of innovation, unlike with something like Tencent or even Kaspi, is virtually non-existent – especially since it's in Kuwait. One has to look no further than the US schools to see just how resilient the institutions have been over centuries, and Humansoft is no different. There isn’t going to be a sudden innovation that will pull hundreds of thousands of students out of schools (not even online learning). So, we have a business that is 1) imperative to the functioning of the economy, and is even more important in a case like Kuwait’s and 2) faces essentially zero disruption. ROE is consistently above 35% and has averaged around 45% - 50% over the last couple of years.

It is hard to calculate the exact market share (in terms of students) of AUM, but we know that it is – by a fairly wide margin – the largest one and most universities are in the 2,000 - 5,000 range. KAMCO Invest estimated the market share to be around 42% in 2021 (among private universities). AUM is obviously much smaller than Kuwait University, but again these don’t compete with each other. AUM, in a way, is a solution to the issue of KU – to some extent. We also have to keep in mind that Vision 2035 planned to add more universities. Although these will likely be public and land in the same category as KU, they will inevitably compete for the same “pool” of income high-school graduates.

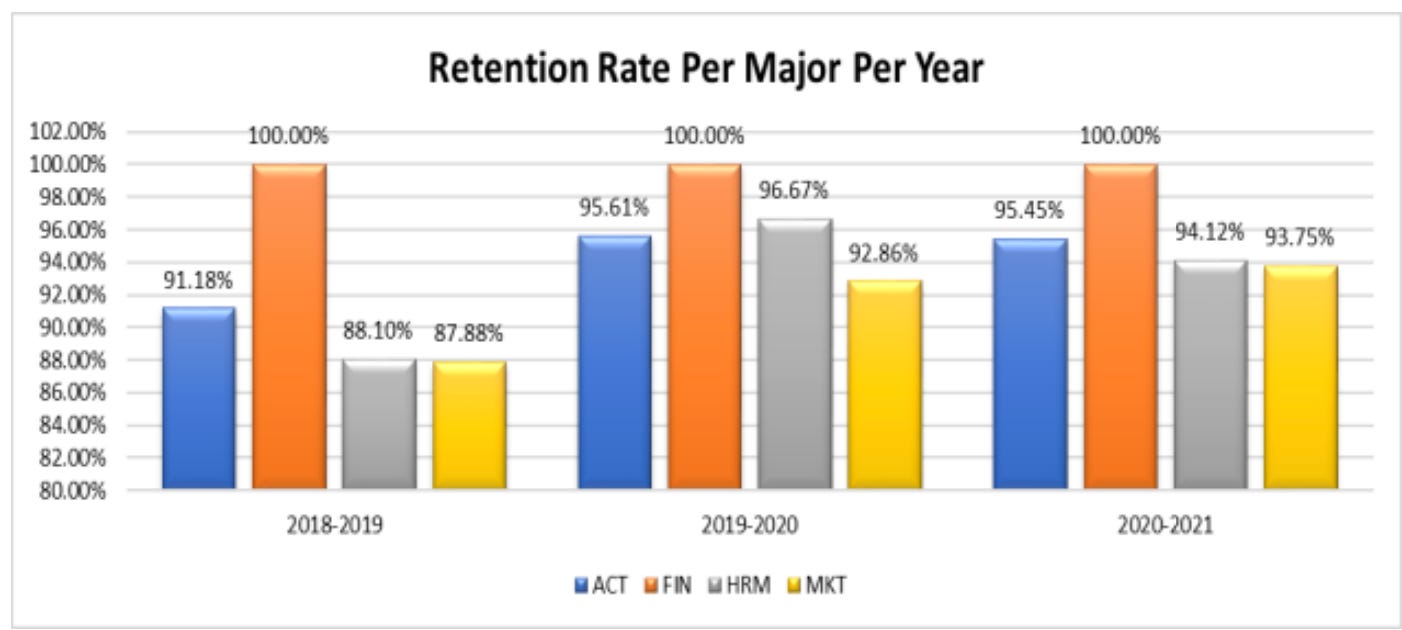

Once a student enrolls in AUM, they are essentially paying a “subscription fee” for the next 2-4 years. Retention rates are pretty solid (depending on the specific program) so it is fairly easy to predict what the next few years of the student base will look like.

Management has a simple pathway for capital allocation: improve existing operations through investments in faculty and technology, build-out the College of Health Science and College of Nursing, and return excess cash to shareholders. I hope that management abandons its e-learning segment – as it has been doing gradually over the recent couple of years. E-learning isn’t as “local” as universities, and I can’t think of a way where it becomes a large enough part of the business to be considered worthwhile. Perhaps management will think of something, but I wouldn’t bet on it given that they’ve had decades and nothing significant came out. I do think secondary education is worth looking at. The systematic issues are just as prevalent, and there are obvious synergies between the two business lines.

There are a couple of barriers to entry that I see in the industry:

Licenses and Partnerships

Institutions have to gain licenses to begin teaching, and then additional licenses on top of that to open various schools. As we have seen, they also need to partner with a top-200 ranked school. This means that the university will have to 1) be of a certain quality to warrant a partnership and 2) have the right infrastructure, faculty, and leadership in place to attract partner institutions. Even then, they will only be on “equal footing” with the likes of AUM and AUK.

Costs

Universities are a fairly capital intensive business, especially during the build-out/ investment stage. Building the campus, leasing land, acquiring equipment, and scouting and hiring faculty all takes time and significant resources. Given the existing teacher shortage, I see the latter as perhaps the most challenging. All of this, obviously, can be done – but it’s not cheap.

Government

Government has been careful in letting foreigners enter the country and own companies. It first allowed full ownership in 2013, but even then it is subject to the approval of the Kuwait Direct Investment Promotion Authority. I highly doubt they would let outside companies come in and take over education, but who knows? Perhaps that’s exactly what Kuwait needs to solve its issues. Given the current policies, however, it seems like competition will primarily be local and limited to a handful of large players.

There are a couple of other barriers (reputation, relationships/ network, alumni, etc.) that I see, but the point is that it is not easy to come in and steal market share quickly.

Certain studies have also mentioned that the country has to shift away from social sciences (which tend to get students the highest paying jobs, especially if they study English and literature) and more towards STEM-based programs. This is in order to facilitate the shift to a “knowledge economy” that the government keeps mentioning, but not pursuing in practice. AUM, given that it has one of the best and largest engineering schools, stands to benefit from this transition.

Kuwait University has also been reaching full capacity recently and has been struggling to expand and accommodate demand. Habib Taher Abul, General Secretary of the Private University Council, stated that “as tertiary education enrollments rise, we are seeing increasingly that public universities at their current capacity are unable to meet demand.” Once again, this is a trend that favors AUM in the long term.

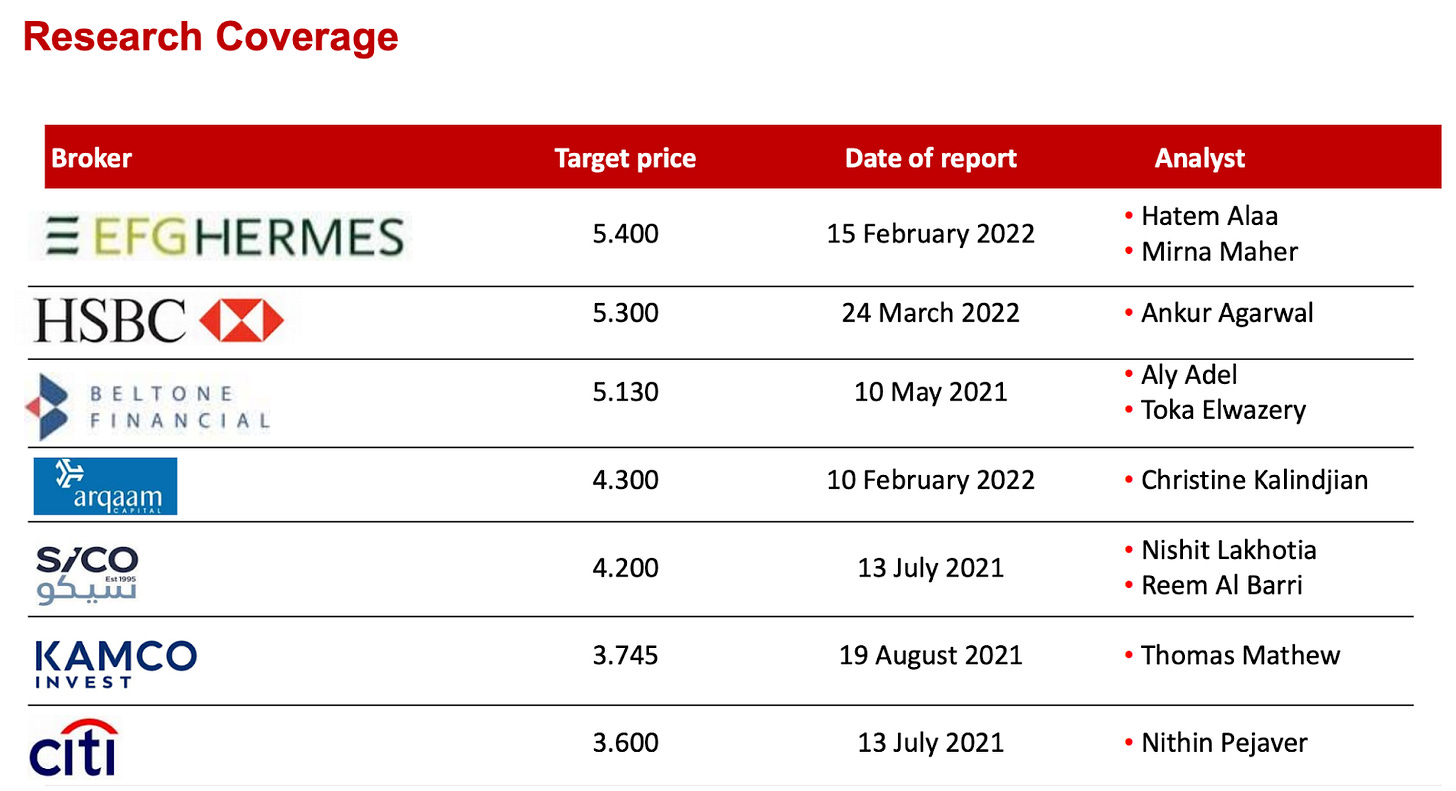

Valuation

Here is where I don’t get as comfortable. At a current market cap of roughly 416 KWD (~$1.3b), Humansoft leaves too small of a margin of safety.

Despite tremendous historic growth, I think it makes more sense that the student base remains relatively static at ~14,000 to (maybe) ~14,500 students. Given that the company has also invested virtually nothing into its infrastructure (CAPEX just ~ 0.6% of revenue for the last 3 years), it again seems like management is not looking for the same aggressive growth it has enjoyed historically.

The company trades at around 8x earnings and 6x -7x at normalized earnings (adjusting for COVID-19’s impact of shifting the school calendar). Let’s first try an EPV approach:

I don’t think it makes sense to calculate average revenue for the last 10 years as the business isn’t as cyclical and is very stable in retaining and growing its student base. I think averaging the last three years makes more sense. So, average revenue for the last three years was around $270mm.

Average operating margin for the three years is roughly 60% (operating margins have consistently been improving) but let’s assume 55% here. So, we get roughly $148mm in operating income. Taxes have been very favorable, with the average effective tax rate just around 1%. I don’t see why this favorable treatment should not exist going forward. Humansoft does, however, also need to make payments to various organizations and initiatives (KFAS, NLST, and Zakat). Total payments were $5.9mm this year and $5.6mm last year. These depend on the earnings of the corporation, but assuming no growth we can just assume $6mm going forward.

Depreciation has averaged ~ $10mm, but CAPEX has been very lumpy. Now, given that virtually no investments into growth are being made, we get an average CAPEX for the three years of just $1.5mm. Assuming that the company will continue investing for growth in the future, however, I think taking the 10 year average here makes sense. Average CAPEX is around $18mm. Although we can try and separate this into growth vs. maintenance, I’ll just use the full figure to be conservative.

So, we get roughly $134mm in earning power, or $1.34b at 10x. To this we can add our net cash position of $223mm (the balance sheet is super clean) to get a conservative EPV of ~ $1.5b, or roughly what the market cap is.

I also tried DCF, assuming a 4% growth rate for the next 5 years, and got roughly $2b - $2.5b. Obviously, the two valuations differ a lot. FCF is slightly inflated given the lack of capital expenditures. If we assume that these will remain so low, then the DCF calculation makes more sense. I, however, doubt that CAPEX will be so low given the future infrastructure investments needed for both of the new colleges/ programs.

At the same time, we get a solid dividend yield of 9-10% that has been growing consistently over the years.

Given the lack of coverage + trading on the Boursa Kuwait exchange, many will find this company to be uninvestable. The business itself, however, is incredibly resilient with strong tailwinds and fine economics. Unless some unusual and extremely unfavorable law comes to pass – which in my view is almost impossible given the importance of private colleges in Kuwait’s education system – there is minimal chance of significant permanent loss. Given all these factors and what seems like a fair price, I think Humansoft can comfortably deliver low double-digit returns over the long-term thanks to just dividends alone. I think this one is worth taking a look, especially for those comfortable jumping into foreign markets.