Note: I’ve been trying to cut down on the word-count as the post is too long for email, but even after removing over 1,000 words the write-up is still too long. I’ll link my full write-up at the very bottom — thank you for reading.

Introduction

Foot Locker isn’t a “wonderful” business. It competes in an industry filled to the brim with competition and its largest supplier, Nike, has just cut back on the amount of product FL is going to receive going forward. Just looking at the headlines, Foot Locker’s story doesn’t seem too great.

What, then, can possibly make Foot Locker a company worth looking at? The answer is price. As Walter Schloss said: “Price is the most important factor in relation to value.” What do we receive, as business owners, for the price we are being offered to buy the company for?

Even though FL isn’t a business with wonderful economics, it is, upon closer analysis, a decent company run by competent management that has been returning cash to SH hand over fist. Its strategy and capital allocation are simple and, as we will discuss, work on reinforcing FL’s competitive position and improving efficiency. When you consider the recent acquisitions of the company, mixed with its management and its generous share buyback and dividend policy, FL appears to be a “Heads I Win, Tails I Don’t Lose” type of bet.

I’m assuming that most are familiar with FL, so I’ll leave a link for those that want to read about the company.

History

To understand FL and its competitive position today, we must first look at its history.

Although FL’s story starts all the way back in 1879, it really picks off in 1963, when F. W. Woolworth – one of the most successful retailers in the 1900s and a pioneer of the modern discount store – acquired one of the largest shoe retailers at the time: Kinney Shoes. Operating Kinney as its subsidiary, Woolworth went on an acquisition spree in the late 1970s and 1980s – acquiring retailers like Foot Locker, Champs Sports, Afterthoughts, and others. The company would play around with various in-mall retail concepts and churned through its banners until it found what really worked. Foot Locker was among a few retailers that produced consistently solid results for the company.

By the 1990s, however, Walmart had begun dominating the retail/ department store space across the US and, subsequently, Woolworth’s market share began to dwindle until it finally closed its last store in 1997. By that time, Woolworth’s shoe business had grown to substantial proportions, and Foot Locker (partially due to the decline of the core business) made up to 70% of total sales. That same year, the company continued making strategic acquisitions, adding Eastbay (one of the largest athletic sportswear retailers at the time) to its family of banners. By 1998, seeing that its shoe business was one the few viable and growing subsidiaries left, Woolworth decided to rename itself Venator Group, operating and growing its shoe business among other minor operations.

Eventually, Foot Locker would grow to such a substantial portion of the business that the company renamed itself Foot Locker Inc. in 2001 and started doubling down on the hot and rapidly growing sneaker market in the US. FL would primarily target younger customers (teenagers) and would focus on offering sportswear primarily around fashion/ lifestyle and not necessarily athletic use.

Here’s a brief timeline I made.

A History of Poor Acquisitions

Here is where the story gets interesting (and a bit messy). Seeing its shoe business explode, FL began rapidly expanding through – in my opinion – foolish acquisitions. Generally speaking, we want management to allocate capital in a way that allows it to earn high returns (above COC if possible). This, in turn, means that it should primarily deploy its capital in markets where it enjoys some form of competitive advantage (in FL’s case it was scale and brand in the US sneaker market) that would shield its excess returns from being competed away. At the very least, we want returns that are in line with cost of capital. Destroying value through substandard capital allocation – instead of returning it to SH – is a big no-no.

For FL, solid allocation would mean focusing on developing its supply chain and logistics network, reinforcing its brand, improving geographic store density to gain economies of scale, and – potentially – expand into adjacent markets and geographies. Let’s see how the company performed:

In 2008, management acquired CCS (California Cheap Skates), a retailer of skateboards and skateboard-related apparel, for $103mm (which, given the size of the business, was too high of a price from the start). This, obviously, was a market FL had no expertise in other than the fact that it targeted a younger audience. Its advantage in the sneaker market did not, in any way, transfer over to its CCS operations, and the company had to sell off CCS for pennies to Daddies in 2014. CCS was essentially mismanaged into the ground. Almost all the $103mm has been burned away instead of being returned to shareholders or invested in improving operations.

Following some disappointing results, the board brought on Ken Hicks in 2009 (currently the CEO of Academy Sports) to clean things up. Hicks, seeing that FL had no business entering the skateboard market, began looking for other ways for FL to expand and, quite logically, landed on Runners Point Group – a German retailer of running shoes. After opening several stores across Europe, FL realized that, once again, its competitive advantages and knowledge of the sneaker business did not translate well to its Runners operations (sneakers running shoes) and it was forced to close down stores.

On the other hand, Side Step, which was part of Runners before being acquired by FL, has performed fairly well. Side Step, in contrast to Runners, was a retailer that focused more on sneakers. Hence, FL’s experience and knowledge could be leveraged to expand Side Step despite the geographic barriers, and the company has actually opened a total of 11 stores over the last three years.

Hicks also went on to open SIX:02 – a women’s athletic fashion retailer. On paper, this seemed like a solid idea, yet the women’s athletic market was already overcrowded and dominated by the likes of Nike, Adidas, and even FL Lady’s stores to some extent. SIX:02 was essentially a start-up brand with no advantage (other than FL’s backing and favorable shelf-space) that was going to be up against entrenched market behemoths. It never succeeded in carving out a niche or gaining a large following, and, as you can probably already tell, SIX:02 was a substandard venture and was closed in 2019.

Capital Allocation

So, here we have a history of poor – or at best decent – capital allocation where management consistently “diworsified” into random markets instead of enhancing its competitive position in an already highly-competitive industry. This history of poor acquisitions shows that FL’s only decent results have come from markets where FL had the advantage in terms of scale and industry and geographical knowledge. Side Step and Footaction show that FL can actual perform well with acquisitions as long as it sticks to what it knows.

Finally, Mr. Johnson was appointed CEO in 2014. Johnson has, for the most part, shown very solid capital allocation. He focuses on remodeling stores (customer experience and sales/store increase), improving logistics (efficiency), and growing the DTC business – which is, as of now, FL’s more logical point of expansion. In 2018, FL invested $100mm in GOAT, an investment that works incredibly well with FL’s existing business and gives it a new channel for distribution.

In 2019, FL introduced a new, reworked membership program called FLX. Once again – a sound and logical point of expanding FL’s brand loyalty and customer retention. Over just 2+ years, FLX managed to gain over 28 million members who have shown to spend 75% more and have order values 10% higher than the average customer. What’s more, the FLX program allows FL to collect data and better tailor customer experience. Johnson is yet to make a poor, value-destructive acquisition or venture.

Johnson and his team’s capital allocation today is leagues above what FL has managed before. And the cherry on top: FL has returned an average of $550mm to shareholders through dividends and share repurchases every year. They have also remodeled a total of 1,144 stores since taking over in 2016 (granted, the program was underway well before Johnson came in). Here is the breakdown of FL’s stores over time.

So, while FL went on to close 642 stores since 2011, its sales/store revenue has actually been increasing thanks to the effective remodeling and some minor tailwinds (see “Sales per Store”).

Moreover, the company has recently divided its NA business into separate regions overseen by their own individual managers. This transition highlights FL’s focus on a hyper-local, customer-driven in-store experience. The shift to off-mall stores also allows FL to deliver better customer service, experience higher traffic, and move away from the overcrowded (and dying) malls across the country.

Industry Economics and Competitive Advantage (not)

It would be a stretch to say that Foot Locker is a business with a wide moat – or any sort of moat for that matter. The retail industry is notorious for intense price competition and with DTC making its way as an increasingly larger part of the consumer’s journey, it’s even harder now for companies to differentiate themselves.

There are, however, certain benefits (and there aren’t that many) in being primarily a sneaker retailer. First, the sneaker business (Jordan, Reebok, Common Projects, and Vans to name a few) is incredibly competitive. Although Nike currently dominates the scene, many brands pour tens of millions of dollars every year into producing the next “hot thing.” Hence, the sneaker industry is one of rapid change and requires significant investments in design and advertising every year just to stay on par with competition. Retailers like FL don’t need to make many of these investments and aren’t subject to the risk of rapid innovation. All they do is, essentially, pivot along with whichever way demand is headed. The main differentiator, then, is scale, customer experience, and store location. Few retailers can establish genuine economies of scale. Hence, FL must focus on effectively managing inventory (which we will touch on later), growing its DTC business, and making sure customers have a good experience in their stores. Sneakers will always be in demand, and the sneaker brands will continuously work on creating better, more exciting products.

Let’s try and talk more specifically about FL now.

FL, first of all, has a certain brand and culture that some people are drawn to – even with all the other options they have available. The black-and-white referee T-shirts, the focus on sneakers and all the hype surrounding the product, and the emphasis on basketball all help differentiate FL from its competitors. If anything, the success of FLX and its large social media following highlight just how widely-followed the company is.

FL has also positioned itself as a fashion brand first and an athletic brand second. People don’t go to Foot Locker to buy sports gear or golf clubs – they go there to buy sneakers or apparel that they want to wear, regardless of if it’s for sports or not. In this sense, FL is operating in a slightly different market compared to some of its competitors and, consequently, is looking to attract a slightly different demographic (although these overlap for the most part). As Lauren Peters (former Foot Locker CFO) stated, “Foot Locker is phenomenal at engaging the customer. We create a customer experience that works as a competitive advantage for us: People like to come into our stores, and they like to touch and feel and see our product.” (2021 Q1 Earnings Call) The fact that over 50% of sales come from buyers who make over 4 footwear purchases over two years highlights the brand’s customer retention. 4x over 2 years at 50% of sales might not seem like much, but we have to keep in mind that the average buyer now has more retailer options available than ever before, and yet many still choose to shop at FL.

What’s more, FL has managed to grow its DTC business, return cash to SH, and remodel its stores while retaining a Fort Knox like balance sheet with an average of $850mm in net cash.

Recent Acquisitions

I think FL’s two recent acquisitions are crucial in understanding why the current market pricing doesn’t make much sense. Let’s go over them one by one.

atmos

atmos, founded by Hommyo-san in 2000, is a digital premium brand in Asia. It offers FL a solid entrance into the Chinese and Japanese markets (where it already started expanding with its other brands). 60% of atmos’s revenue comes from digital sales. Here’s an extract from a company filing:

“atmos is a digitally led, culturally-connected global brand featuring premium sneakers and apparel, an exclusive in-house label, collaborative relationships with leading vendors in the sneaker ecosystem, experiential stores, and a robust omni-channel platform.”

Here’s another quote from its press release:

“The company expects to grow atmos annual sales by approximately 50% to nearly $300 million during the next three years by scaling in existing markets and expanding internationally.”

So, we can assume atmos is making ~ $200mm in sales. At a purchase price of $319mm net of cash acquired, FL paid just 13x earnings for a business that it expects to increase 50% in the next three year and have a solid runway after that. Assuming it does manage to grow to $300mm in sales and retains its 16% EBIT margin, we’re looking at an after-tax addition of over $30mm to the bottom line! I think FL has seen that it can succeed internationally in the sneaker market, as seen with Side Step and several other brands, and so atmos becomes a logical acquisition. By acquiring a digital retailer, FL can avoid the gap in local market and real estate knowledge (as well as lack of local relationships) and allow Mr. Hommyo-san to continue expanding the business with a now larger pool of capital.

WSS

Just like atmos, WSS is an acquisition that falls squarely within FL’s circle of competence. Here’s an extract:

“WSS is a U.S.-based off- mall athletic footwear and apparel retailer, focused on the Hispanic consumer, which operated 93 stores at the acquisition, primarily on the West Coast. The aggregate purchase price for the acquisition was $737 million paid in 2021, net of cash acquired. We believe that this acquisition enhances our growth opportunities in North America and creates further diversification and differentiation in terms of both customers and products. WSS is expected to reach $1 billion in annual sales by 2024, supported by accelerated store openings and anticipated strong same-store sales growth.”

Eurostar allows FL to gain a meaningful Hispanic demographic that otherwise might not be part of the FL banner family. This isn’t the SIX:02 or CCS type of acquisition that does nothing to reinforce FL’s core market. Instead, this acquisition allows FL to gain market share, add a demographic which it can also begin introducing to its other brands, and serves as another option for growth. What’s more, it supports FL’s transition to off-mall stores. Let’s now look at the purchase:

According to the company, WSS made $650mm in 2022 (which makes sense given the back-to-school + holiday seasons). Assuming the lower range of its EBIT margin (11%), WSS earns around $50mm after-tax. At a purchase price of $737 net of cash, FL paid around 14.7x earnings for a company that it, again, expects to grow double-digits as FL begins scaling the business.

Nike and Foot Locker’s Shift

Brands like Nike and Adidas will always dominate the sportswear market. Nike has wiped the floor with its competitors over the last decade and will likely continue to do so in the future (if only the company was a bit cheaper!!!). Nike has a phenomenal brand that is only growing stronger, and retailers have grown accustomed to depend on Nike’s product like a drug. Nike, however, began cutting some of its contracts, including Belk, Dillard’s, Zappos, Boscov’s, and others. All in all, the company has cut off 50% of its wholesale accounts since 2018 (ouch). Like so many other retailers, Nike pushed towards a DTC shift in 2011, and DTC accounts for as much as 40% of its overall sales. Here’s how it performed:

As Nike grows its business, it can afford to cut more and more accounts. This strategy makes a lot of sense. Not only does Nike now realize higher margins on its products (wholesale vs. retail) but it has now cut-off a large supply of Nike products, meaning that it unlocks more pricing power and, subsequently, even higher margins. What’s more, moving its own product allows Nike to have better control over customer experience and the way the Nike brand is perceived. With its ecosystem of apps and websites, Nike can collect more data and have a better grasp of what the consumer needs (in terms of both product and CX). Nike, then, thrives at the expense of poorer, smaller retailers. In fact, Nike’s DTC business alone generates more than its competitors make in wholesale + DTC. Here’s what the company said recently:

“Nike has a bold vision to create the marketplace of the future, one closely aligned with what consumers want and need. As part of our recently announced Consumer Direct Acceleration strategy, we are doubling down on our approach with Nike digital and our owned stores, as well as a smaller number of strategic partners who share our vision to create a consistent, connected and modern shopping experience.”

Let’s see where FL fits in all of this:

For FL, Nike has accounted for over 75% of supplier spend over the years – like so many other retailers, FL has developed a dependency on Nike (and more specifically its Jordans). Now, Nike will account for no more than 55% of supplier spend (partially because Nike cut back and partially because FL is going to try and diversify). Given that Nike has been cutting off various accounts for years now (and FL’s stock price largely went nowhere), the main risk that the market sees is that Nike can continue to cut-off FL until it doesn’t receive any more of Nike’s product (or substantially less than it used to). Let me walk you through why I think this likely won’t be the case:

1: Nike and Foot Locker partnership

Nike and FL have been partners for decades, and FL remains one of its larger, more significant retailers. Over the years, the two companies have collaborated on exclusive projects and programs and have recently launched a drop-ship program together. Unlike Dick’s or Hibbett, Foot Locker offers Nike an outlet towards a slightly different demographic, and FL has a very strong position as a sneaker retailer. Mr. Johnson has mentioned on several occasions that “Nike will remain an important partner” and that the two companies will continue working together. It is, hence, unlikely that Nike will cut-off FL at some point soon. Sure, it’s a possibility, but I’m willing to bet big that that won’t happen.

2: Nike Still Needs Retailers

As a Nike executive said, “We have to look for retailers who are investing in themselves and creating great consumer experiences because that is a part of partnerships — it can’t be Nike alone. Those partners and independents that have great followings — and there are cult-like followings behind some of our partners — we will stay with them. They make us better.”

Nike benefits from certain partnerships and suffers from others. Since it has no control over what the customer experience is like in those outside retail stores, it must pick and choose those banners that it believes will reinforce its brand. If Nike just suddenly pulls out of all shops, its brand is going to suffer. People need constant exposure to Nike, and the only way (at least for now) for the company can accomplish that is through careful partnerships with retailers. What’s more, if Nike leaves a store, then that store is going to look for other brands to fill up that hole in demand. Adidas, Reebok, and New Balance will swoop in to grab that extra shelf-space and gain more exposure and volume in the process.

Nike wants its retailers to have a solid customer experience that they are also continuously working on improving. Foot Locker fits that description perfectly.

3: Size

FL too large for Nike to be able to dismiss easily. Generating around $8.9b in revenue and being historically dependent on Nike means that FL has accounted for a large chunk of Nike’s wholesale efforts. Nike cannot just toss out a retailer that is responsible for billions of dollars in sales. Not only that, but cutting off FL will likely end up hurting both companies in the long-run. The space Nike leaves behind will be quickly filled in by someone else and, consequently, that space will be hard to take back if Nike suddenly needs to have its products on FL’s shelves again. FL’s large DTC network also gives Nike a strong foothold in e-commerce that some of FL’s competitors simply cannot match. It is unrealistic to think that Nike can just toss FL out from its retailer base.

“Fine,” you might say. “Perhaps Nike won’t just leave FL entirely – but it can still continue cutting back on the amount of product FL receives!” Sure, it can, but on top of the reasons mentioned above, we have the following:

1: FL is aggressively diversifying its supplier base

Since Nike made its cut-back, FL has 1) reached an agreement with ABG to be an exclusive retailer of some of the Reebok products, 2) partnered with Deckers to sell Hoka this summer and 3) entered into a strategic partnership with Adidas where the two companies will be working on building new products, expanding existing franchises, enhancing customer experience, and accelerating FL’s push into apparel. The Adidas partnership is targeting $2b in retail sales by 2025.

In some sense, having Nike cut-back is a good thing. Depending on just one supplier for over 75% of your product spend is not a strategy that leads to solid and stable long-term results. It is as if management was suddenly awakened by Nike’s shift and began rapidly doubling-down on its other brands, as well as pulling in new ones. As Mr. Johnson said, “Foot Locker is under-penetrated in virtually all of our other brands outside of our top three.” As Nike left a $1b hole in FL’s budget (according to Matt Powell from NPD Group), other retailers are going to try and grab that space, perhaps on even more favorable terms as they compete with one another for FL’s shelf-space.

2: FL can come out as a winner in the Nike DTC shift

Although Nike cut back on FL, it also entirely closed many of its other partnerships (over 50%). This, in turn, means that FL will now have a larger “market share” of Nike products distributed through retailers, even while moving less of its product. People are starting to notice that some of their favorite stores no longer sell Nike (remember, Nike is like a drug), and they’ll go out looking for a retailer that they know will have fresh Nike products and good customer service. Consumers generally want to find a handful of stores that they can just go and shop at whenever they need to, and Foot Locker is going to capture a lot of that moving traffic.

Here’s a nice quote I found from a Telsey analyst while reading through Retail Dive’s articles (which I really recommend, especially Cara Salpini’s):

“Despite the loss of Nike, Foot Locker’s strategic shift to add more brands and be less dependent on one vendor, transition its store base to off-mall locations, and participate in new revenue streams like resale with GOAT make sense and should strengthen the company’s position in the marketplace [and] add shareholder value over time.”

Management

Mr. Johnson joined FL all the way back in 1993, meaning he’s been with FL for almost 30 years now. In fact, he spent more time at the company that Foot Locker Inc. existed as a business!

After joining, Johnson quickly made his way up the corporate ladder, becoming President and CEO of Footlocker.com/ Eastbay (the two main DTC channels at the time) in 2003. In 2007, Johnson served as the head of Foot Locker Europe. In 2010, under Ken Hicks, he was named CEO of the brands Footaction and Foot Locker – and was promoted to president of the whole retail group just one year later. Finally, he was named CEO of the company in 2014, and was appointed Chairman in 2016.

Clearly, Mr. Johnson has extensive experience in both sports retail and, more importantly, in running Foot Locker. He was in all the roles necessary to drive FL forward today: Head of DTC, Head of Retailing, and Head of Europe. His experience at Eastbay and Footlocker.com is reflected in how efficiently FL managed to scale its DTC business, and how well atmos (primarily a digital retailer) fits in the picture. The success of Side Step and FL EU is also likely due to his time as head of the European division early on in his career. After all, there’s a good reason why the EU has been a net store opener while other stores in Canada and the Pacific decreased or remained flat.

I also liked the fact that the team noticed that the Footaction stores were in close proximity with one other retailer from the portfolio (usually Foot Locker) and that the two were directly competing with one another. They also noticed that Footaction stores generated lower sales, had lower margins, and generally saw less traffic than its other banners. Hence, management decided to close and remodel (⅓ were rebranded) the stores in an attempt to optimize efficiency and boost overall margins. Lots of CEOs often focus on the “vision” and growth without first looking at ways to improve the existing, underlying business. Johnson’s investments in logistics, remodeling, and DTC (while also carefully managing inventory and making opportunistic investments) all highlight his and his team’s focus on the quality of the company and its operations, not simply its growth. This is also supported by some impressive numbers:

Valuation

Let’s first look at some of FL’s stats, compare FL to its competitors, and then try and determine a range of values we think FL should be trading at.

Dick’s has footwear as a relatively small part of its business: only 21%. Footwear accounts for 55-60% of sales for Hibbett, and over 80% of sales for FL. It is also important to remember that competition strength and competitive advantages should be assessed in relation to the best, most efficient competitor – not just any retailer. Dick’s has performed very well over the last couple of years and has been rewarded by Nike with more programs + stable (and perhaps even growing) product flow. Consequently, Dick’s valuation is a lot higher than FL’s.

On top of these, there are obviously the e-commerce retailers like StockX and GOAT, as well as the behemoths Nike and Adidas (mostly Nike though). These companies have very different business models, however, and it would be hard to compare them to FL. The sports retail industry has limited barriers to entry, is generally price-competitive, and is as overcrowded as it has ever been. FL enjoys scale and brand recognition, but so do many of its competitors.

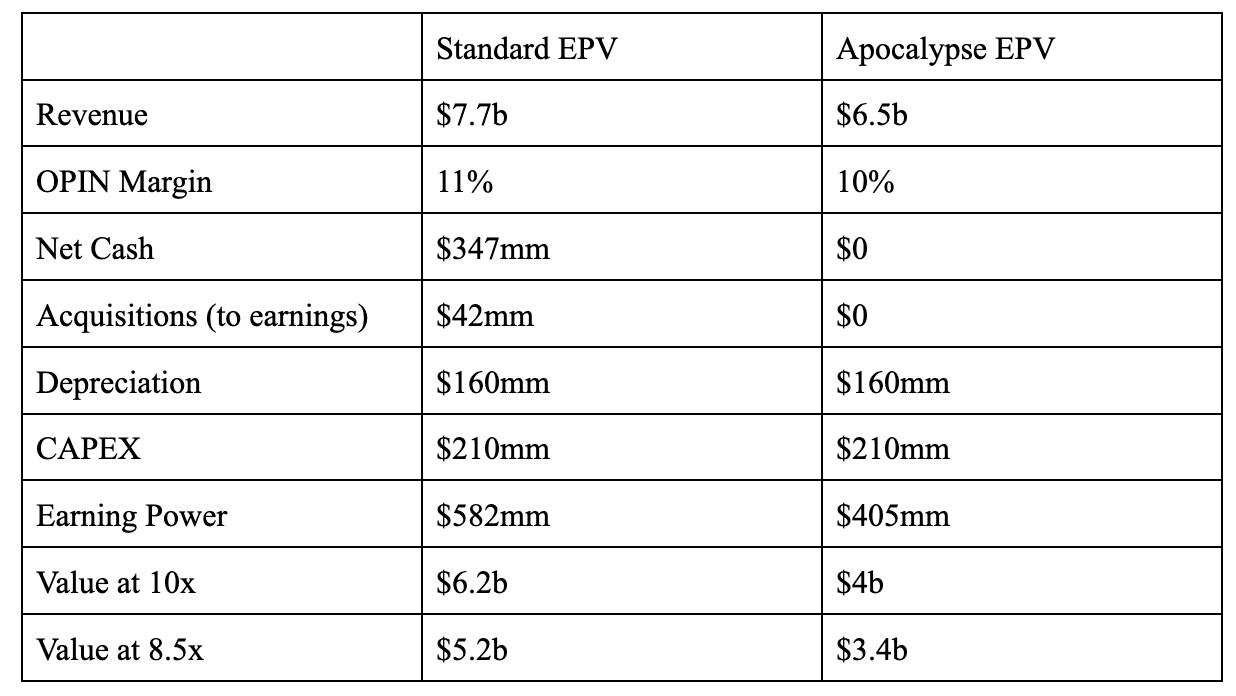

Given that FL has averaged around $7.5b in sales over the last 10 years and around $8b in the last five years, let’s assume that, before all the Nike issues, FL could generate sustainable revenue of around $7.7b (down ~ 14% from current levels) thanks to all the efficiency and logistics investments it has made plus the growing stream of revenue from its DTC channel. Assuming a historical operating margin – on the lower end – of 11%, FL can then earn around $590mm after-tax. FL’s average CAPEX for the last 10 years has been around $210mm. I don’t want to try and separate CAPEX into maintenance vs. growth as, given the competitive environment, FL likely cannot afford to not make these growth investments. Hence, all of its CAPEX is “necessary.” So, adding back the $160mm in average depreciation over time and subtracting the total CAPEX figure from our after-tax operating income, we get around $540mm in EP ($590mm + $160mm - $210mm).

To this “historic” earning power we can also add FL’s recent acquisitions. In absolute terms, assuming FL’s two acquisitions work out, atmos and WSS will generate a combined $1.3b in sales by 2025 and contribute roughly $120mm to the bottom line. To be conservative, let’s assume that the $7.7b in sales already includes the current results of WSS and atmos (mentioned above). If management manages to scale these businesses appropriately (which it should), the company should then see around a $500mm addition to FL’s top line and about a $42-45mm addition to its bottom line. This, then, gives us an earning power of about $582mm. At $582mm and a no-growth multiple of 8.5, we get around $5b in EPV. To this value we add our net cash position of $347mm and we get ~ $5.35b in EPV.

But wait! Isn’t Nike supposed to hurt FL? Aren’t sales supposed to decline? As Francisco García Paramés said: “Think. Don’t Build Models.” We cannot build a model that can accurately predict the impact of Nike’s shift on Foot Locker (no one really can) – but we can think about what downside the current valuation implies, and how that compares to historic performance.

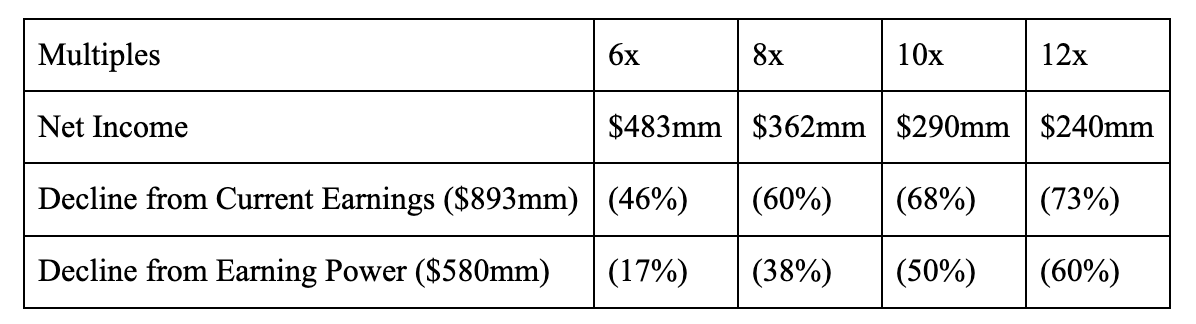

Here’s what the current valuation implies FL will earn in the future across a range of multiples:

So, current levels of valuation imply that the company will, at least, see its current income decline by 46% and its earning power decline by 17% over time. This would also be a sustainable decline, i.e., FL’s earning power will now be somewhere between $250mm to $480mm. We can assume that a 6x multiple isn’t sustainable unless things get even worse, so an 8x - 10x is more in the “likely” range. The beauty of having a margin of safety is that we get a cushion from unfavorable events developing. In other words, buying at a current valuation would mean that we only lose money if current earnings or EP decline FURTHER than the levels priced in above.

We have assumed that a lot of things will go well in the EPV valuation above. Let’s now assume the following: sustainable revenue is $6.5b (the lowest it’s ever been since 2014), recent acquisitions don’t work out, and operating margin is at the rock-bottom of the average range: 10%. Let’s also assume that Mr. Johnson retires, and a poor CEO comes in and starts diworsifing, erasing the net cash position of $347mm in the process. We would get the following:

Let me just add a bit more perspective on the $7b in revenue. The last time FL generated less than $7b in revenue was in 2013, when it made roughly $6.5b in sales. Here’s a side-by-side (sorry for all the tables) of FL today vs. back then

FL is a very different business now than it was in 2013. With a new CEO, improved capital allocation, two strong acquisitions, and improved operational efficiency, today’s Foot Locker is, fundamentally, a stronger and more resilient business than it was 8 years ago.

So, even at $0 net cash, two ruined acquisitions, and a low operating margin, we still get ~ $3.4b.

But there’s more! FL has been buying back shares continuously over the past decade. Shares outstanding decreased from 154mm in 2012 to 103mm in 2021. In other words, almost ⅓ of all outstanding shares have been bought back over ten years! FL bought back an average of ~5mm shares a year. Let us assume, for a moment, that the buyback continues even at a slow, moderate pace of 3mm a year instead of 5mm. We would still see an annual (and increasing) 3% decrease in shares outstanding. On top of that we get a $150mm dividend payment (adjusted for post-COVID), or a ~ 5% yield. Hence, cash return alone, without organic growth or active reinvestment, is already at > 8%. Of course, this doesn’t take into account the impact of Nike, but FL should be able to continue share repurchases and its $150mm+ dividend payments even with lower revenue and income to work with.

FL, as we have talked about, isn't necessarily a bad business – but quality is not really the key factor here. The market is pricing FL as if its recent acquisitions, generous buyback and dividend policy, and sound capital allocation are worth nothing. The market has come to a consensus that Nike will wipe FL out from the retail landscape, even with the fact that 1) Nike will continue selling through FL, 2) FL will now have a larger share of Nike products distributed through retailers, 3) FL began aggressively diversifying its supplier base and partnered with several very strong brands, and 4) FL has made two excellent acquisitions which will drive substantial growth going forward.

Now, will FL still be around and thriving in, say, 10 years? I don’t know; however, the recent market price gives us a ridiculous risk-reward proposition, not even considering the buybacks or acquisitions. I have noticed a tendency in the general market to easily write-off companies without really taking the time to look into them. It’s easy to say, “Nike will kill Foot Locker,” but few really pick apart the situation and the relationships, competitive positions, and improving underlying operations of the company. Just like with the idea that “GameStop is dead,” “Airbnb will wipe out hotels,” or “EV charging stations will kill existing convenience stores,” people make significant generalizations without really understanding the underlying story. Sure, these might play out in the distant future, but that doesn’t mean that the cash flow and performance of the company over the next several years could just be ignored.

In fact, as we have seen, we don’t even have to place bets on whether the acquisitions will work out or whether Mr. Johnson will continue effectively allocating capital. Instead, we are simply betting on the fact that Nike won’t hurt FL to the extent priced into current valuations, and that’s a bet I’m willing to take.

Personal Note:

Despite how attractive FL is, I always have to think about opportunity cost. How does FL compare to my first, second, third, or fourth best idea? Is FL as good of a business as Kaspi.kz, Alimentation Couche-Tard, Alibaba, Facebook, or even Yandex (despite it being a Russian company)? The answer, at least for me, is no. Foot Locker is clearly a much cheaper business, but, as a business owner, I know that it is the underlying, long-term fundamentals and performance of the company that truly drives successful investing. Although it’s highly likely (we can never be too confident or 100% sure) that FL will drive strong returns over the next couple of years, I want to own businesses that will ultimately thrive over the long-term -- businesses that can consistently reinvest their incremental earnings at high returns, protected by formidable barriers to entry. I still hold some FL (average price is ~ $28), but it is in my “cigar butt” pile that serves more as practice in analysis and valuation (and I just find it really fun as well). For those interested in the company, I suggest diving in and forming your own thesis. Unlike with wonderful companies where you can, as Mohnish Pabrai says, “focus on the big picture,” cases like FL call for careful and diligent analysis. This is simply what I have found over several weeks of research. I think the odds are skewed enough in our favor for us to comfortably place a bet – but of course that won’t be the case for everyone. Thank you for reading! Here’s the full write-up.